This ETC Short reviews the commitments made during COP26. This is an updated version of the Short published on 12/11/2021 which reviewed the commitments from the first week of COP26.

The Paris climate accord committed the world to limit global warming to well below 2°C and ideally to 1.5°C. If we are to keep that possibility of 1.5°C alive and make it certain that we will stay below 2°C, we need not only to head towards a net-zero global economy by mid-century but make big emissions reductions in the 2020s.

Ahead of COP26 we at the Energy Transitions Commission set out six sets of actions which could build on NDCs to achieve the reductions required, set out in our report Keeping 1.5°C Alive: Closing the gap in the 2020s. The report highlighted technical and economically feasible actions which, if realised, would reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by around 45% and methane (CH4) emissions by 40% by 2030, putting a 1.5°C pathway within reach.

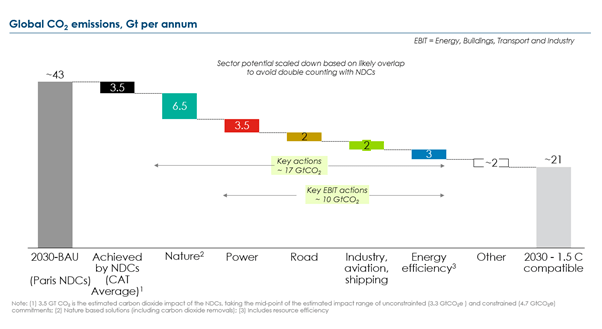

On a business-as-usual pathway global CO2 emissions could reach ~43 GtCO2 in 2030. If we are to maintain a pathway which is consistent with limiting temperature increase to 1.5°C global emissions will need to fall by ~22 GtCO2/year by 2030, alongside a ~150 Mt/year reduction in methane. Of the 22 GtCO2/year gap, only ~3.5 GtCO2/year in reductions was pledged in national commitments (Nationally Determined Contributions), taking a mid-point of unconditional and conditional national pledges (ETC estimated a further 20 MtCH4 are included in NDCs, equivalent to 0.5 GtCO2e if using a 100-year).13.5 Gt CO2 is the estimated carbon dioxide impact of the NDCs, taking the mid-point of the estimated impact range of unconditional (3.3 GtCO2e) and conditional (4.7 GtCO2e) commitments from Climate Action Tracker’s (CAT) Emissions Gap estimates as of November 2021. The ETC’s Keeping 1.5C Alive report used an older assessment from CAT, which suggested a range of 2-5 GtCO2e resulting from NDCs.

Beyond NDCs, we estimate ~17 GtCO2/year of feasible emissions reduction potential could be achieved in the 2020s, with an additional 6.6 GtCO2 of reductions delivered by “Nature-Based Solutions” and ~10 GtCO2 via accelerated reduction of emissions from the energy, building, industry and transport sectors (Figure 1). These emissions reductions estimates are scaled down in order to try to avoid double-counting with actions already included in NDCs.2The ETC approach in this analysis was the same for our Keeping 1.5C Alive report, where we scaled back the additional impact of action in the 2020s to try to account for what is already included in NDCs, recognizing that quantifying what is included in NDCs for each sets of actions is challenging. Although this is not an exact science, we believe most double counting between the announcements and the NDCs is avoided. Further detail on our methodology can be found on p28 of the main report and p15 of the technical annex found here: https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/keeping-1-5-alive/ Each additional action in the 2020s has been scaled back according the following factors: • Nature based solutions (incl. Carbon removals): Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs • Decarbonising the power sector: Assumed 20-30% of action is already covered in NDCs • Decarbonising road transport: Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs • Supply-side decarbonisation in other sectors: Assumed 5% of action is already covered in NDCs • Energy and resource efficiency: Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs

If these savings can be delivered in addition to existing commitments within the NDCs we can in principle close over 90% of the gap between a business-as-usual scenario and a 1.5°C aligned trajectory. These commitments at COP26 complement existing NDC commitments, focusing on the highest potential areas for short-term action, and can generate the momentum for future reinforcement of NDCs over the next year.

Figure 1: Key actions required to reduce CO2 emissions in 2030

Source: Energy Transition Commission “Keeping 1.5oC Alive” (2021)

The question after the many new commitments arising from COP26 is, how close are we to closing the gap?

COP26 saw a flurry of announcements and headlines across a range of issues, as well as updates to NDCs. Climate Action Tracker’s estimate of emissions reductions in 2030 resulting from NDCs increased from 3.5 GtCO2e to 4 GtCO2e between September and November 2021, reflecting new or updated NDCs from China, South Korea and others. Additionally, key agreements were unveiled in multiple areas – including methane, nature, road transport and coal – to varying degrees of specificity and tangibility. Equally varied were the lists of signatories; although all of the policy agreements contained backing from several big economies, each also had notable absences.

This ETC Short reviews the commitments agreed upon during COP26, and assesses how much of the emissions gap could be covered by announcements made during COP26, if these announcements are then fully delivered in the next decade.

Methane

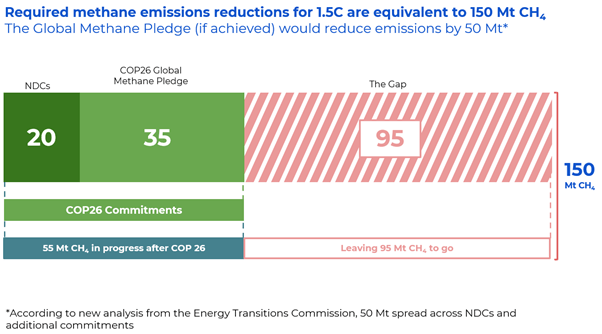

In Keeping 1.5°C Alive, the ETC estimated that in addition to ~20 MtCH4/year of actions already promised in NDCs for 2030, methane emissions could be reduced by a further 130 MtCH4 – bringing emissions down 40% relative to today’s levels. During the first week of COP26 more than 100 countries joined the US and EU in committing to the Global Methane Pledge, which seeks to reduce CH4 emissions by 30% by 2030, relative to 2018 levels. The countries signed up to the pledge account for ~45% of global CH4 emissions today.

Summary impact: If each of the signatories succeeds in reducing their own methane emissions by 30%, total annual emissions would decline by ~48 MtCH4. However, given that the US, EU and Canada have detailed methane reduction strategies in development, there is likely to be a high level of overlap with NDCs.3Russia and Iran are large methane emitters given their gas production and reliance on very old, leaky gas transmission infrastructure. China is the world’s number one CH4 emitter, owing to its rice paddies and coal mines. The US is also a large methane emitter, and a 30% reduction in US methane emissions would reduce CH4 emissions by around 9 Mt. Whilst no explicit detail on methane reductions was included in the US’s April NDC, further details have recently been stated in the recent Long-term Strategy Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan, suggesting a reduction of up to 8 MtCH4 could be possible by 2030. The ETC’s original estimate suggested that 48 MtCH4 of emissions reductions could occur in addition to NDCs. We have revised this estimate down to 34 MtCH4 reflecting that methane strategies in the EU, US and Canada have a high level of overlap with NDCs (in line with analysis by the Climate Action Tracker). These countries would account for 14 MtCH4 of the emissions reductions under the Global Methane Pledge. Given, this we have included just 34 MtCH4 of the 48 MtCH4 as additional to NDCs. That is a good start but falls short of the 130 MtCH4 of additional potential identified by the ETC in Keeping 1.5°C Alive. In part this shortfall reflects the absence of some of the world’s largest methane emitters, including Russia, China and Iran.

Figure 2: Impact of the Global Methane Pledge

Nature

The ETC estimates that emissions from deforestation, coastal and peatland degradation could be reduced by 4.6 GtCO2/year by 2030 (3.6 Gt from avoiding deforestation and 1.0 Gt from avoiding coastal and peatland degradation). Week 1’s “Nature Day” saw more than 130 countries – including countries with large forest areas such as Brazil and Indonesia – sign up to the Leaders declaration on Food and Land Use (FLU), which pledged to end deforestation by 2030, accounting for ~85% of the world’s forests. This was supported by a FACT dialogue statement signed by multiple countries supporting increased supply chain transparency, with a view to avoiding deforestation.4Forests, Agriculture and Commodity Trade dialogue. See: https://ukcop26.org/forests-agriculture-and-commodity-trade-a-roadmap-for-action/ Funding was also dedicated towards supporting Indigenous peoples and local communities, and advancing their land tenure rights.

However, a similar pledge was also put forward in 2014, signed by 37 countries, and deforestation rates have since increased. Similarly, the ETC’s Keeping 1.5°C Alive report suggested that achieving the full 4.6 GtCO2/year savings by 2030 could require up to US$200bn per year in finance, but the funding committed behind these pledges falls far short of this (currently at less than $20bn, spread over the next four years). Furthermore the statement does not detail how the implementation of the agreement would be tracked, or what might happen if nations renege on the promise. While the commitment itself is a step forward, delivering it – including the required finance – is a huge priority. If delivered, we estimate this pledge could cut emissions by an additional ~4.0 GtCO2/year by 2030.

In addition to deforestation, a total of 45 nations signed on to a new Policy Action Agenda, designed to help policymakers deliver the necessary changes to agriculture (amongst other agricultural initiatives). However as this was not accompanied by specific targets or actions, we have not been able to estimate the impact of these agriculture announcements on emissions reductions.

Summary impact: After scaling down our estimated impact of avoiding emissions from deforestation to account for double-counting in existing NDCs, we estimate total potential savings in 2030 from Nature could, if delivered, reduce emissions by around 3.5 GtCO2/year in 2030 beyond the limited amount of avoided deforestation that is estimated to be currently included in NDCs.5Of this, avoiding deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia account for around 0.8 GtCO2/year and 0.5 GtCO2/year respectively. CAT estimates suggest NDCs in these countries account for, at most, up to 0.2 GtCO2/year of emissions reductions. Separately, CAT estimate the impact of this pledge to be just 1.1 GtCO2/year in 2030. The main differences between our estimate and CAT’s is that CAT exclude emissions reductions from countries that previously signed the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, and also exclude Indonesia, where there has been uncertainty around whether Indonesia reversed its commitment to the FLU declaration.

Coal and power sector decarbonisation

The ETC’s Keeping 1.5°C Alive report estimated that 3.6 GtCO2/year could be avoided from coal power generation in 2030: 0.7 GtCO2 from no further construction of coal fired power plants, 1.2 GtCO2 from phasing out existing coal in OECD by 2030, and a further 2.3 GtCO2 from early phase-out of older generation in non-OECD countries.

COP26’s Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement saw more than 40 countries commit to ending all investment into new coal power generation domestically and internationally. Signatories from developed economies also pledged to phase out coal power in the 2030s whilst emerging economies would phase out during the 2040s.

Although this provides some signals that “the end of coal is in sight” there are several major caveats to note:

- First, the phase out dates may not be as ambitious as is required for a 1.5°C pathway. Keeping 1.5°C Alive (and other similar reports including the IEA Net Zero Report) notes the need for coal to be phased out by 2030 for advanced economies (2040 for Rest of World), not during this decade. The deadlines in the current statement are around 10 years behind this.

- Second, the list of signatories was a mixed bag. New commitments from large and growing Asian emitters Vietnam and South Korea were a welcome surprise to many observers. Indonesia’s pledge came with the stipulation that the country will finish building some new coal plants before its stopping altogether, but this still represents significant progress from even one year ago.

- Less encouragingly, Poland, signed up but made clear its target date for final phase out is 2049 – no different from its existing timeline. And of course missing were both China and India, neither of which signed up to the statement but account for the vast majority of the new coal pipeline, and large volumes of existing coal.

Together therefore, we estimate the impact of this initiative at just 0.2 GtCO2/year in 2030.

Together therefore, we estimate the impact of this initiative at just 0.2 GtCO2/year in 2030.

However other initiatives that focus on the power sector provide confidence that further emissions reductions could be possible here. For example, further signatories signed up to the Powering Past Coal Alliance – a group of countries, sub-national entities and businesses focusing on the phase-out of existing coal, a crucial priority if we are to meet 2030 targets – the Race to Zero6The Race to Zero campaign aims to accelerate private sector action on climate. Each Race to Zero breakthrough is gaining agreement on ‘Breakthrough ambitions’ from a critical mass of companies in each sector. These ambitions are expected to scale over time, in order to achieve longer-term outcomes (2030 targets) and goals (beyond 2030). So far ‘breakthrough ambition’ has been achieved in 17 sectors, with more announcements expected soon. Where the Race to Zero breakthroughs overlap with the ETC’s analysis, we were able to estimate the impact of the agreed ‘breakthrough ambitions’, based on the assumption that the agreed ambitions – announced by ~20% of companies within specific sectors – are able to lead to the suggested outcomes in 2030.commitments from businesses to scale up renewables (see below), and the innovative South Africa coal finance deal.7Although South Africa didn’t sign up to the Coal-to-Clean transition statement, the start of its phase-out supported by several western states was announced in week one of COP26, highlighting the importance of climate finance in delivering an early exit from coal (as noted in the Keeping 1.5C Alive report). If the ambition underlying these initiatives were fully delivered by 2030, we estimate this could add a further 1.25 GtCO2/year of emissions savings.

Summary impact: Our estimate suggest that commitments to no new coal will reduce emissions by just ~0.2 GtCO2; just ~5% of the potential we assessed in our report, due to the absence of big emitters such as China and India. However further initiatives in the power sector have the potential to deliver a further 0.75 GtCO2/year of emissions reductions in 2030, if fully implemented. Accounting for the potential impact that is likely included in existing NDCs, these commitments could add just under 1 GtCO2/year beyond current NDCs.8An earlier version of this note estimate emissions reductions from the power sector at 1.2 GtCO2/year and road transport at 1.5 GtCO2/year. We have scaled back both of these estimates to account for overlap between these initiatives and CAT’s latest assessment of NDCs.

Road Transport

The ETC’s Keeping 1.5°C Alive report identifies ~2.6 Gt of potential CO2 savings in the road transport sector by 2030. Driving this is a ban on all sales of ICE light-duty vehicles by 2035, combined with city-based action to restrict the use of existing ICE vehicles beyond defined future dates. Together these could lead to around 20% of cars on the road being electric by 2030 and deliver around 2 GtCO2/year of reductions. An additional 0.6 GtCO2/year of savings could be possible improved heavy-duty truck efficiency.

The COP26 declaration on zero emissions cars and vans was signed by a range of countries and non-state actors, however although India signed the declaration (with a statement focusing on two wheelers) several other major markets, such as China, the US and Germany were missing from the country declaration. It was however supported by a range of automakers (though Ford, GM, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo) and other important non-state actors (through California and New York states, some Australian states and other large cities).

Summary impact: Our estimates suggest that the commitments to electrification already made by auto manufacturers – whether within the Race to Zero framework or outside of it – alongside country commitments to end the sales of fossil fuelled vehicles imply that road transport electrification for light-duty vehicles will go much faster than most NDCs assume. This will likely deliver an additional 1.25 GtCO2 beyond NDCs in 2030 (after scaling back to avoid double-counting). Of this, only around 0.1 GtCO2 of emissions reductions is included in country commitments made at COP26 through the declaration on zero emissions cars and vans.

Industry and energy efficiency announcements

Four major economies – Australia, Indonesia, Japan and Nigeria – signed onto the Product Efficiency Action Plan, aimed at rapidly improving the energy efficiency of products sold around the world. This brings the total number of signatories to 14, covering approximately 50% of the total emissions reduction potential. The plan sets out to double the efficiency by 2030 of products in four key areas: lighting, refrigerators, air conditioners and industrial motor systems – which together account for over 40% of global electricity demand. If fully realised, this is likely to deliver an additional 0.2 GtCO2/year of emissions reductions beyond NDCs in 2030.

Separately, Race to Zero ambitions on cement and aviation were agreed. If fully implemented these would likely lead to around 25% of concrete production being carbon neutral by 2035, and Sustainable Aviation Fuel making up 10% of all aviation fuel in 2030, leading to emissions reductions or around 0.3 GtCO2/year beyond what we estimate is included in NDCs.

Related initiatives include the Clydebank Declaration for Green Shipping Corridors signed by 22 governments and the US-led First Movers Coalition, which supports breakthrough technology deployments (incl. Sustainable Aviation Fuels) through demand-side commitments from private sector actors.

Other notable initiatives announced at COP26

Countries representing ~70% of global GDP signed up to the “Breakthrough Agenda” which seeks to reduce the cost of clean technologies by 2030 in four key sectors: power, road transport, steel production and hydrogen. The COP parties also committed to develop global metrics to enable tracking of progress of both state and non-state initiatives, led by the IEA, IRENA and HLC in collaboration with other international initiatives (including Net Zero Steel Initiative for Steel).

Lastly, Mark Carney unveiled the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (or GFANZ) – a global coalition of leading financial institutions committed to accelerating the decarbonization of the economy. The purpose of GFANZ is to hold the financial community accountable for its pivotal role in addressing climate change. It is made up of 450 institutions from around the world that have $130 trillion worth of assets under management – the ambition is to align these assets with Net Zero commitments.

Though these initiatives support the core COP26 initiatives identified above, we haven’t included any specific quantification of these initiatives.

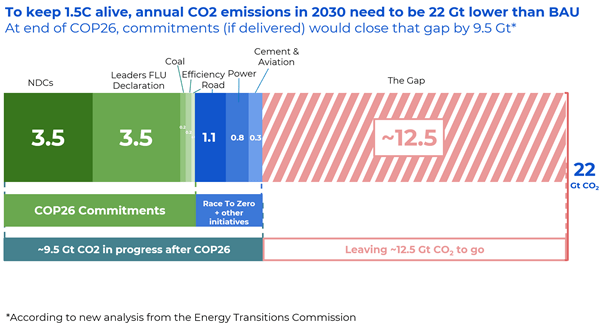

Summary of announcements at COP26: 9.5 Gt in progress and to be delivered, 12.5 Gt to go

Emissions reductions from the signatories of the Global Methane Pledge, could lead to emissions reductions of around 35 MtCH4, beyond the 20 MtCH4 we estimate is included in NDCs. Together, this would account for just over a third of the total emissions reductions potential to 2030 we identified in our Keeping 1.5ºC Alive report.

For Carbon Dioxide emissions, existing NDCs are likely to contribute around 3.5 GtCO2/year to the 22 GtCO2/year emissions reduction gap in 2030 – around 15% of the gap.

If delivered, we estimate the initiatives announced at COP could add a further ~6 GtCO2/year of emissions reductions in 2030 beyond NDCs, closing a further 30% of the gap. This estimate includes:

1. The COP26 country-level initiatives: representing an additional 4.0 GtCO2 – 20% of the gap

- 3.5 GtCO2 from leaders declaration on Forestry and Land Use,

- 0.2 GtCO2 from the Global Coal to Clean Power Transition Statement

- 0.2 GtCO2 from the Product Efficiency Call to Action

- 0.1 GtCO2 from the country commitments in the declaration on zero emissions cars and vans

2. Country, company and financial sector commitments,9This includes commitments from companies in key sectors that will deliver emissions reductions announced before Glasgow, but which were not considered as part of the Energy Transition’s analysis in September estimating a 22 GtCO2 gap. This reflects that changes in the real economy are accelerating action on climate change beyond country NDCs. including those made as part of Race to Zero have the potential to deliver an additional 2.2 GtCO2 – 10% of the gap

- 0.75 GtCO2/year in the power sector

- 1.1 GtCO2/year in the road transport sector

- 0.3 GtCO2/year in the aviation and cement sectors

Together, the impact of all pledged NDCs and additional action from commitments at COP26 could close around 45% of the gap between a business-as-usual scenario for CO2 emissions in 2030, and a 1.5ºC aligned pathway.

Figure 3: Summary of commitments to reduce CO2 emissions

The additional commitments made at COP26 are important steps in the right direction, but will require additional finance and committed action from public and private sector parties in order to be successfully delivered.

Together these actions can close around 45% of the gap between a business-as-usual scenario in 2030, and a 1.5°C consistent pathway. The crucial test of these commitments is how they are turned into concrete action, and the best mechanism for this would be for countries to increase ambition in future NDCs. The NDCs announced at COP26 were the first revision to NDCs since the Paris Agreement in 2015, and future revisions weren’t expected until the mid-2020s. However the Glasgow Climate Pact advances this timeline substantially, by formally requesting parties to strengthen their NDCs, alongside an annual ministerial meeting on ‘pre-2030 ambition’. Recognising this, parties should build on the momentum agreed through initiatives at COP26 across both public and private sectors and update their NDCs in 2022 to reflect the additional progress.

Overall, we’re not able to go home from Glasgow saying job done, and we are not currently set to achieve the full 22 gigatons we need. But we have new commitments which will make a difference and which must be delivered, and we have a springboard for further progress which we must achieve over the next few years sector by sector, and reflect in improved NDCs from next year.

Technical Notes

[1] 3.5 Gt CO2 is the estimated carbon dioxide impact of the NDCs, taking the mid-point of the estimated impact range of unconditional (3.3 GtCO2e) and conditional (4.7 GtCO2e) commitments from Climate Action Tracker’s (CAT) Emissions Gap estimates as of November 2021. The ETC’s Keeping 1.5C Alive report used an older assessment from CAT, which suggested a range of 2-5 GtCO2e resulting from NDCs.

[2] The ETC approach in this analysis was the same for our Keeping 1.5C Alive report, where we scaled back the additional impact of action in the 2020s to try to account for what is already included in NDCs, recognizing that quantifying what is included in NDCs for each sets of actions is challenging. Although this is not an exact science, we believe most double counting between the announcements and the NDCs is avoided. Further detail on our methodology can be found on p28 of the main report and p15 of the technical annex found here: https://www.energy-transitions.org/publications/keeping-1-5-alive/

Each additional action in the 2020s has been scaled back according the following factors:

- Nature based solutions (incl. Carbon removals): Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs

- Decarbonising the power sector: Assumed 20-30% of action is already covered in NDCs

- Decarbonising road transport: Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs

- Supply-side decarbonisation in other sectors: Assumed 5% of action is already covered in NDCs

- Energy and resource efficiency: Assumed 10-15% of action is already covered in NDCs

[3] Russia and Iran are large methane emitters given their gas production and reliance on very old, leaky gas transmission infrastructure. China is the world’s number one CH4 emitter, owing to its rice paddies and coal mines. The US is also a large methane emitter, and a 30% reduction in US methane emissions would reduce CH4 emissions by around 9 Mt. Whilst no explicit detail on methane reductions was included in the US’s April NDC, further details have recently been stated in the recent Long-term Strategy Methane Emissions Reduction Action Plan, suggesting a reduction of up to 8 MtCH4 could be possible by 2030. The ETC’s original estimate suggested that 48 MtCH4 of emissions reductions could occur in addition to NDCs. We have revised this estimate down to 34 MtCH4 reflecting that methane strategies in the EU, US and Canada have a high level of overlap with NDCs (in line with analysis by the Climate Action Tracker). These countries would account for 14 MtCH4 of the emissions reductions under the Global Methane Pledge.

[4] Forests, Agriculture and Commodity Trade dialogue. See: https://ukcop26.org/forests-agriculture-and-commodity-trade-a-roadmap-for-action/.

[5] Of this, avoiding deforestation in Brazil and Indonesia account for around 0.8 GtCO2/year and 0.5 GtCO2/year respectively. CAT estimates suggest NDCs in these countries account for, at most, up to 0.2 GtCO2/year of emissions reductions. Separately, CAT estimate the impact of this pledge to be just 1.1 GtCO2/year in 2030. The main differences between our estimate and CAT’s is that CAT exclude emissions reductions from countries that previously signed the 2014 New York Declaration on Forests, and also exclude Indonesia, where there has been uncertainty around whether Indonesia reversed its commitment to the FLU declaration.

[6] The Race to Zero campaign aims to accelerate private sector action on climate. Each Race to Zero breakthrough is gaining agreement on ‘Breakthrough ambitions’ from a critical mass of companies in each sector. These ambitions are expected to scale over time, in order to achieve longer-term outcomes (2030 targets) and goals (beyond 2030). So far ‘breakthrough ambition’ has been achieved in 17 sectors, with more announcements expected soon. Where the Race to Zero breakthroughs overlap with the ETC’s analysis, we were able to estimate the impact of the agreed ‘breakthrough ambitions’, based on the assumption that the agreed ambitions – announced by ~20% of companies within specific sectors – are able to lead to the suggested outcomes in 2030.

[7] Although South Africa didn’t sign up to the Coal-to-Clean transition statement, the start of its phase-out supported by several western states was announced in week one of COP26, highlighting the importance of climate finance in delivering an early exit from coal (as noted in the Keeping 1.5C Alive report).

[8] An earlier version of this note estimate emissions reductions from the power sector at 1.2 GtCO2/year and road transport at 1.5 GtCO2/year. We have scaled back both of these estimates to account for overlap between these initiatives and CAT’s latest assessment of NDCs.

[9] This includes commitments from companies in key sectors that will deliver emissions reductions announced before Glasgow, but which were not considered as part of the Energy Transition’s analysis in September estimating a 22 GtCO2 gap. This reflects that changes in the real economy are accelerating action on climate change beyond country NDCs.